As the Palo Alto City Council considers, once again, a strict limit on new office development in the city, one homegrown employer will be watching closely: Hewlett Packard Co.

The tech giant is in the process of splitting itself into two firms — HP Inc. and Hewlett Packard Enterprise. In a letter to the city, an executive said the goal is for both offshoots to stay in town. But that would be harder to do should officials restrict growth.

"…a limit of this magnitude would effectively eliminate Palo Alto as a headquarters location should additional office or R&D space be a necessity," wrote Lorin Alusic, director of corporate affairs for HP in the western region.

Backlash against development is growing across Silicon Valley, notably in Cupertino, where some residents have joined to oppose redevelopment of Vallco Shopping Mall; and Los Gatos, where a recent campus expansion for Netflix Inc. featured an epic battle for development permissions.

The growth-limit debate, always an undercurrent in Silicon Valley, caught fire in Palo Alto last year in reaction to a number of deeply unpopular development proposals. Residents also pushed back against the city's "planned community" zoning process, where property owners can win bigger projects in return for negotiated public benefits (some of which, residents argue, never happen).

It culminated last fall in the election of two new slow-growth council members, and the annual office cap idea was brought forward last month as a discussion item. It returns to the fore at today's meeting.

Growth-control advocates say Palo Alto has simply not planned well enough to handle the city's burgeoning office market, among the strongest in the country — and that Palo Alto, historically an enclave of Stanford University researchers and salaried engineers, is losing its soul.

But the prospect of limiting new office space has raised alarm among developers, urbanists, major employers, property owners and real estate industry players, who say the city could squelch economic activity — or even make the problems of growth worse — should it move forward with a broad growth limit.

"There will be less supply," David Van Atta, a real estate attorney with Palo Alto-based Hanna & Van Atta, told me. "If the demand stays, rents are likely to go up — or certainly not go down. So this town will risk not being capable of susstaining new businesses."

The cap concept has generated deep resistance from Stanford University, which owns the 10 million-square-foot Stanford Research Park. Corporate heavyweights like VMware and SAP have written letters to the city opposing an office cap.

Meanwhile, a recently formed grassroots group, Palo Alto Forward, is proposing a different approach— targeting traffic in the form of trip reductions rather than square footage and urging a broader conversation about transit and housing.

It's unclear exactly what a specific office cap proposal would look like; council members at this point are simply talking about whether to go down this path. At the last council meeting where the cap was discussed, Vice Mayor Greg Schmid made a motion for city staff to study an annual cap between 10,000 and 45,000 square feet; it didn't move forward as a majority of council members wanted to finish the conversation before making a recommendation.

To get a handle on the possible ramifications of an office cap, I reached out to academics, developers, brokers and land-use attorneys. I also consulted planning officials in cities that have existing growth-management schemes, and discussed concerns about development with a slow-growth activist. Here are some takeaways.

What's the problem?

Longtime Palo Alto resident Cheryl Lilienstein is part of Palo Altans for Sensible Zoning, a community group that supported two candidates who were elected to the council — Tom DuBois and Eric Filseth. Lilienstein says when she first moved to the city several decades ago, she enjoyed a small-town charm filled with artists, musicians and families. Now, she said, much of the culture has left — more specifically, been priced out — "and when rush-hour comes, I duck and cover."

"If you live here, trying to get across town is incredibly difficult," she said. "People are just amazed that you could live three miles from work and it can take you 30 to 45 minutes to get there."

Palo Alto has seen about 540,000 square feet of office space built between 2008 and 2015, or roughly 67,000 square feet per year, according to a city staff report. (In the same time, it lost about 70,000 square feet of retail.)

That's not a huge amount of new office space compared to cities like Sunnyvale, which have approved millions of square feet of new commercial development in recent years. But Lilienstein said the city hasn't adequately beefed up parking capacity or roadway infrastructure. Downtown workers now regularly park on residential streets. Rents and housing prices have skyrocketed. Then there are the less tangible losses, such as the city's changing look and feel, Lilienstein said.

"We want this environment to remain a beautiful place," she said. "As big buildings go up, the beauty is obliterated. One reason we were drawn here is it was beautiful.

"We have that experience of those ugly things cropping up and going, 'Oh my god.'"

Would an office cap work?

Lilienstein's concerns are shared by Mayor Karen Holman, who in her state of the city address last month cited the loss of retail space to office as a major concern. She said that in addition to an office cap, the city is considering an interim ordinance to protect retail on California Avenue.

But would an office cap be effective?

Experts I talked to said it depends on what the cap is, and what the goals are.

A limit on new office development by square footage could slow the worsening of traffic somewhat, experts said. But David Blackwell, a partner with Allen Matkins in San Francisco, said other uses, such as retail and residential, also affect traffic. "And traffic isn't a local problem; it's a regional problem," said Blackwell, who leads the law firm's land use practice group.

"It's not a perfect salve," he added. "The problem with caps, in my view, is they're blunt instruments. It's used to solve a problem but not in the most sophisticated way. It doesn't take into account different needs for different areas."

There's also the issue of employers packing more workers into the same amount of space — something that would not be alleviated by an office cap.

Gary Pivo, a professor at the University of Arizona who has authored papers on growth control measures, says an office cap could end up slowing the rate of development, and, therefore traffic congestion. But there's a caveat.

"Most of those issues will be put off — but not solved — by slowing the rate of development," he said. "If you get the same amount of office space over twice as much time, then you end up delaying the amount of traffic you generate."

The better option, he said, actually involves more development that conforms to "smart growth" models of planning.

"Honestly, the traffic problem is best managed by a policy of highly concentrated employment centers that are near housing that are balanced — so if you do drive you don't drive so far — and that are concentrated enough to be well served by fixed rail and bus service," he said.

What can be learned from similar growth control measures?

Walnut Creek has had an office limit for many years. But it's difficult to draw conclusions relating to Palo Alto, because the cities are such different markets, both geographically and in terms of demand for office space

Walnut Creek allows 75,000 square feet of net new office a year, doled out every two years, and the allocations are allowed to roll forward if they're not built. Today, there is about 600,000 square feet in the development pool, said Sandra Meyer, director of community development for Walnut Creek. (The city also allows applicants to reserve their allotment out of a future allocation based on their expected construction phasing.)

In short, Walnut Creek's office rents have simply not risen high enough to attract a glut of office development, and developers have never actually run into the limit.

"I don't think it has thwarted development," Meyer said. "The market's not there yet."

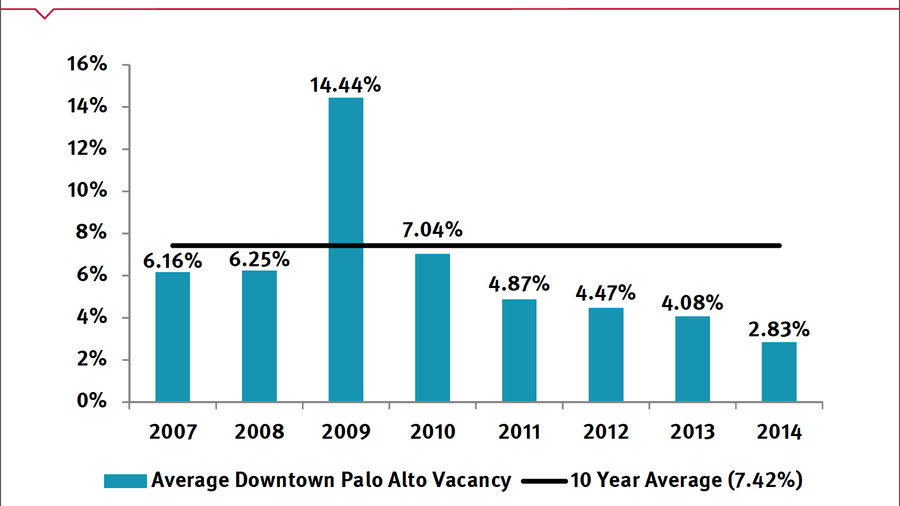

By contrast, Palo Alto's discussion comes as vacancy rates in that city's office market plummet to rock-bottom levels — at the end of 2014, downtown's vacancy rate was an absurdly low 2.83 percent, according to a report prepared by Newmark Cornish & Carey.

That's down from 4 percent a year earlier. For comparison, real estate firm Transwestern pegged downtown Walnut Creek's vacancy rate at 12.3 percent at the end of the fourth quarter. The city's Shadelands business park had vacancy of 25 percent.

Edward Del Beccaro, managing director for Transwestern's East Bay and Silicon Valley offices, agrees that Walnut Creek's cap hasn't thwarted development. However, he said Walnut Creek likely lost Workday, the cloud-based human resources company, to Pleasanton because of the lack of modern, large-floor-plate office buildings in the city.

Would Palo Alto lose its tenants?

That possibility has been cited by office cap opponents. HP's letter notwithstanding, Palo Alto has experience with tenants outgrowing their local options. Facebook Inc. famously grew too big for downtown in 2009, decamping for the Stanford Research Park. Newmark Cornish & Carey's research shows downtown's vacancy jumped to 14.4 percent that year. (A couple years later, Facebook outgrew the Research Park and leased the old Sun campus in Menlo Park.)

"Sooner or later you get to a place where you need more space and can't get it here," Van Atta said. "That leads to the question of the sustainability of the town as a marketplace for developing new business and sustaining new business."

But for cap proponents, it's unclear whether such a possibility is seen as a negative.

"My immediate world does not get improved by saying we need more, more, more here because we're the best," Lilienstein said.

What would happen to rents?

Echoing most experts, Mark R. Wolfe, an attorney with M. R. Wolfe & Associates and a visiting lecturer in Urban Studies & Public Policy at Stanford, said Palo Alto rents would increase as long as demand remains strong. That in turn would probably accelerate changes in the city's tenant makeup.

"You'll see a lot of high-tech, VC-related firms displacing other firms in the long run," Wolfe said.

It gets more complicated, however.

"It's a huge assumption that the demand side will not change," he said. "You also don't know what effect the cap itself would have on the demand side."

Wolfe gave an example: "It could suggest that Palo Alto is anti-business, anti-growth. So new businesses, mindful of the cap, might no longer be interested in locating in downtown Palo Alto. So what would have been a big increase in rent might not materialize."

Pivo said an office cap would not in itself increase rents.

"Rents will go up or not depending on what's going on in the area wide market," he said. "If you're an owner of a building and say, 'There's a limit on, I'm going to crank up the rents,' you're still competing with the wider market."

Of course, if other cities are also tamping down on new space — and demand is growing — one would expect rents to rise across the region.

Who benefits? Who loses?

If you're an owner of an existing office building, you might actually want an office cap. After all, higher barriers to entry generally increase asset prices.

"As long as you're someone who's buying and holding property and not in the development game, you'd arguably benefit," Blackwell said. "But if you're an owner and also a developer, it makes life more difficult."

There's a flip side: An office cap would also depress values for property owners of land that is not yet entitled with building rights, Blackwell said.

"If I'm buying something that has uncertainty, I'd probably demand some concession or reduced price," he said. "So a cap could positively affect properties with already established office uses because they're there. But if you have a property that's not so entitled, it has the opposite effect."

Some possible winners: Cities who want to see more development activity, such as San Jose.

Capital is fluid, so it's possible developers and funders could simply go elsewhere, as long as the deal makes sense.

"Uncertainty is an enemy of development," Blackwell said. "If you try to underwrite a project and you're not sure if there will be any office space available when you want to pull permits, that makes underwriters nervous. Does it make it so they say, 'I don't want to have anything to do with that locality, and I'll go elsewhere'? It's difficult to tell. They might say, 'San Jose is good enough. There's enough going on.'"

What other options are out there?

Palo Alto Forward, a citizens group that advocates for smarter planning, transportation and housing, has come out against the office cap idea.

Instead, it wants to focus on requirements that would mitigate traffic impacts by requiring developers to reduce drive-alone car trips. Fees could also be imposed on commute trips at existing buildings.

Its proposal was outlined in a five-page letter last month. Such ideas are gaining ground, as cities like Mountain View have recently required developers to implement "transportation demand management" programs, such as providing beefed up shuttle programs. Those types of growth control measures are said to be based on "performance," rather than square footage.

"If the concern is vehicle miles traveled, then regulating an office development using that criteria makes more sense than saying we're only going to allow 50,000 square feet," Blackwell said.

Elaine Uang, an architect and member of Palo Alto Forward, said she shares concerns about growth.

"I totally see the parking and traffic concerns," she said. "There's 50 people parked outside blocking my driveway all the time. And I see the businesses I used to go to, go out of business because their rents are being raised."

But she wants to foster a broad-based conversation about strategies to reduce the negative effects.

"For me, the question is, What are the mechanisms and incentives that actually help and make a big difference to reduce parking and traffic, and get people to consider other alternatives?

"How can we see all these things as opportunities?" she added. "How can we enable this whole social milieu that's whirling around, and try to be thoughtful about how we can accommodate all this? I don't believe it's an intractable problem."

Today's meeting starts at 6 p.m. in council chambers. Read the agenda here.

Get the business scoops you need to start the day with our free Morning Edition email.